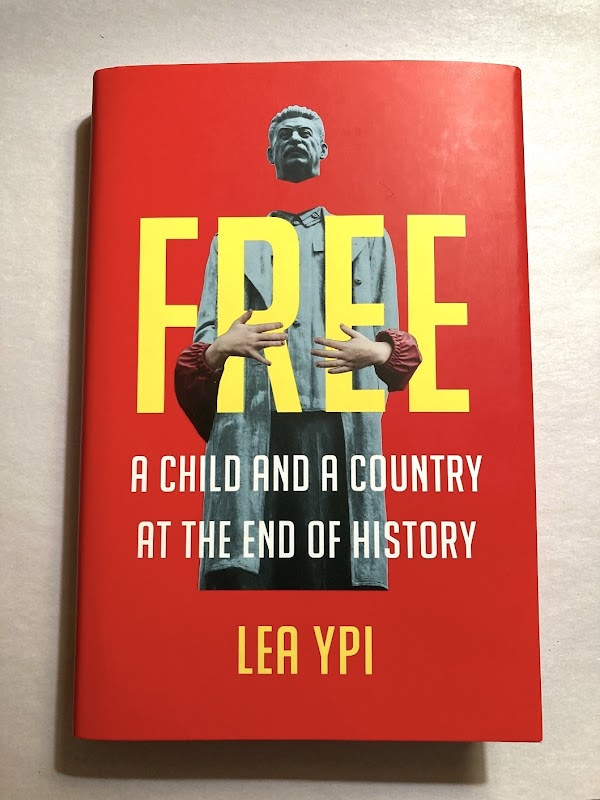

Uma Criança e um País no Fim da História

Lea Ypi escreveu um clássico de leitura compulsiva e altamente recomendado. "Free: A Child and a Country at the End of History" (2022) é um livro de memórias escrito com base na estrutura coming-of-age que nos leva da sua infância à adolescência, enquanto disserta sobre a vida na Albânia nos anos 1980-90, entre os últimos anos do comunismo e os primeiros do liberalismo. Na primeira parte, Ypi regressa à infância, desvelando o modo como o mundo de ideais era criado e mantido ao seu redor pela professora da escola primária e pelas meias-verdades dos pais e avós. Quando em 1990 a ditadura cai, o seu mundo transforma-se, com os seus pais a revelar-lhe que nunca tinham apoiado o partido, nem Enver Hoxha ou Estaline. Ypi descobre do dia para a noite que todas as suas referências tinham sido construídas sobre uma mentira...

O isolamento de décadas conferiu à Albânia um exotismo singular no cenário europeu. Primeiro desligou-se da URSS, depois da China, sempre detestou o Ocidente, por isso vivia orgulhosamente só, a poucos passos da Grécia e Itália. Por isso este livro é tão interessante, porque Ypi abre aqui um canal direto ao passado para nos dar a ver como se vivia ali antes e depois. Aprende-se muito, mas não se pense que é um registo documental, descritivo de memórias. Funciona, porque Ypi tem um talento-nato para contar histórias, para criar personagens redondas a partir dos seus familiares, dos seus amigos, das pessoas com quem conviveu. Em estilo, "Free" é mais romance histórico do que livro de memórias, graças às suas competências narrativas.

Claro que ajuda ter interesse no país, e nomeadamente nas questões relacionadas com o fim do comunismo europeu, porque Ypi usa dessas histórias, dos eventos reais, para de forma subtil realizar grandes quadros sobre os efeitos do comunismo, e depois também sobre o liberalismo. Isto porque Ypi, apesar de ser hoje professor a de Marxismo na London School of Economics, não é uma defensora do comunismo, assim como não é do liberalismo. Ao longo de todo este livro, apresenta antes ambos como condicionantes da nossa verdadeira liberdade, e talvez por isso este seu livro se eleve ainda mais alto, já que dá conta do modo como as ideologias, quando seguidas cegamente tendem à destruição, em vez de aos ideias que professam.

Deixo um excerto alargado do epílogo do livro:

"EACH YEAR, I BEGIN my Marx courses at the London School of Economics by telling my students that many people think of socialism as a theory of material relations, class struggle, or economic justice but that, in reality, something more fundamental animates it. Socialism, I tell them, is above all a theory of human freedom, of how to think about progress in history, of how we adapt to circumstances but also try to rise above them. Freedom is not sacrificed only when others tell us what to say, where to go, how to behave. A society that claims to enable people to realize their potential but fails to change the structures that prevent everyone from flourishing is also oppressive. And yet, despite all the constraints, we never lose our inner freedom: the freedom to do what is right."

(...)

"I no longer needed to count my last pennies until the next scholarship instalment. I could enjoy meals out and drink late in bars, discussing politics with my new university friends. Many of those friends were self-declared Socialists—Western Socialists, that is. They spoke about Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky, Salvador Allende, and Ernesto “Che” Guevara as secular saints. It occurred to me that they were like my father in this respect: the only revolutionaries they considered worthy of admiration were the ones that had been murdered. These icons showed up on posters, T-shirts, and coffee cups, much like how photos of Enver Hoxha would show up in people’s living rooms when I was growing up."

(...)

"My stories about socialism in Albania and references to all the other Socialist countries against which our socialism had measured itself were, at best, tolerated as the embarrassing remarks of a foreigner still learning to integrate. The Soviet Union, China, the German Democratic Republic, Yugoslavia, Vietnam, Cuba — there was nothing Socialist about them either. They were seen as the deserving losers of a historical battle that the real, authentic bearers of that title had yet to join. My friends’ socialism was clear, bright, and in the future. Mine was messy, bloody, and of the past."

"And yet, the future they sought, one that Socialist states had once embodied, found inspiration in the same books, the same critiques of society, the same historical characters. But, to my surprise, they treated this as an unfortunate coincidence. Everything that went wrong on my side of the world could be explained by the cruelty of our leaders or the uniquely backward nature of our institutions. They believed there was little for them to learn. There was no risk of repeating the same mistakes, no reason to ponder what had been achieved, and why it had been destroyed. Their socialism was characterized by the triumph of freedom and justice; mine by the failure of these ideas to be realized. Their socialism would be brought about by the right people, with the right motives, under the right circumstances, with the right combination of theory and practice. There was only one thing to do about mine: forget it."

(...)

"It is easy to say, “What you had was not the real thing,” applying that to both socialism and liberalism, to any complex hybrid of ideas and reality. It releases us from the burden of responsibility. We are no longer complicit in moral tragedies created in the name of great ideas, and we don’t have to reflect, apologize, and learn."

(...)

"My mother finds it difficult to understand why I teach and research Marx, why I write essays on the dictatorship of the proletariat. She sometimes reads my articles and finds them baffling. She has learned to weather awkward questions from relatives. Do I really believe these ideas are convincing? Or feasible? How is it possible? Mostly, she keeps her criticisms to herself. Only once did she draw attention to a cousin’s remark that my grandfather did not spend fifteen years locked up in prison so that I would leave Albania to defend socialism. We both laughed awkwardly, then paused and changed the topic. It left me feeling like someone who is involved in a murder, as if the mere association with the ideas of a system that destroyed so many lives in my family were enough to make me the person responsible for pulling the trigger. Deep down, I knew this was what she thought. I always wanted to clarify, but didn’t know where to start. I thought that it would take a book to answer.

This is that book."

Comentários

Enviar um comentário